This is a two part series of articles in which I address some important topics following the Twelver doctrine of Imamate, this article will be an introduction to this series and the second article will address the Imamate of the Shia Twelfth Imam: Muhammad Al Mahdi. The book I use as reference for this article is from a book written by Abu Muhammad al-Hasan ibn Musa al-Nawbakhti called Shi’a Sects. Abu Muhammad al Hasan is a Shia himself.

See: Coming Soon

As I have repeatedly discussed in previous articles and conversations about the Twelver Shia belief in the 12 Imams, it remains an assertion that is difficult to substantiate due to a significant lack of evidence. This issue has become so challenging for proponents of this belief that many Twelver apologists often resort to attempting to disprove the alternative doctrine that rejects the imamate of Ali ibn Abi Talib (may God exalt his face) because they are under the impression that proving the imamate of one of their imams is sufficient to show that the Muslims who reject the Twelver notion of imamate are upon falsehood.

In other words, it is a common tactic for Twelver Shias to [try to] prove the Imamate of Ali ibn Abi Talib using whatever weak evidence they can find as a means to illustrate that Sunni Islam (which I reference here in this article as the Muslims) is false. As you shall soon see, the concept of “imamate” in the Shia paradigm is a controversial and disputed subject matter, so even when a Twelver Shi’ite tries to prove the “imamate” (whatever their particular notion of imamate may be) of the great Ali ibn Abi Talib, they require a lot of fallicious and poor reasoning.

If you are in the Twelver Shia-Sunni polemics circle, what you have likely seen is that oftentimes, Twelvers are insistent on proving the Imamate or displaying the virutes/superiority of Ali ibn Abi Talib (may God exalt his face) rather than proving the virtues of the latter imams. The reason for this is straightforward: Ali ibn Abi Talib was no ordinary man, a fact that knowledgeable Muslims generally agree upon. However, when it comes to the later Imams, Twelvers struggle to provide convincing evidence that these individuals were divinely appointed and infallible. Moreover, they face even greater difficulty in proving that these Imams were superior to the companions of the Prophet (upon whom be peace), whom Twelver Shias revile.

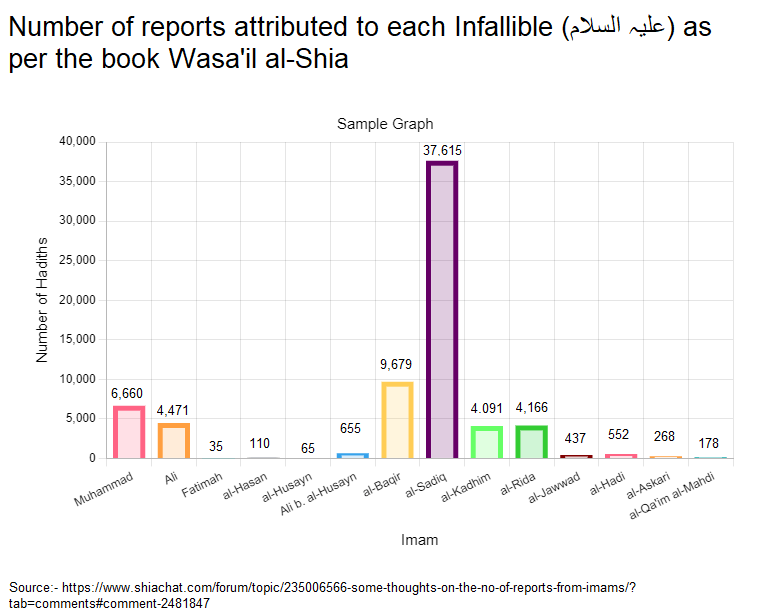

The reason for this is very straightforwards, it simply because Twelver Shi’ites lack any sort of substancial information on these men. Let’s take for example Ali al Hadi, the 10th Twelver Shia infallible, divinely appointed Imam. If we compare the number of reports (hadith) attributed to him, in comparison to Imam Jafar al Sadiq, (may God be pleased with him) we see an odd disparity.

Indeed, it is very odd that Ali al Hadi, whom lived for 40 years, has almost no narrations attributed to him in the Shia corpus in comparison to Imam al Baqir (may God be pleased with him) and Imam Jafar al Sadiq (may God be pleased with him). This dilemma ultimately manifests in the fact that Twelvers have a very hard time knowing anything about him (other than a handful of fabrications attributed to him) and therefore have a hard time proving his imamate.

Having been a Twelver Shia for nearly 17 years of my life, I can confidently state from personal experience that Ali al-Hadi and Muhammad al-Jawad are rarely, if ever, mentioned in Shia gatherings, whereas Ali ibn Abi Talib (may God exalt his face), Hussein ibn Ali (upon him be peace), Hasan ibn Ali (upon him be peace), and Zayn-ul-Abidin (upon him be peace) are almost always central figures in these gatherings.

Before I get into the reason for this disparity and why Imamate is such a tricky doctrine for Twelver Shias to prove, I would like to delve into another tactic that Twelver apologists use to persuade ignoramus into joining their denomination. Of course, Twelver Shias cannot prove this incredibly confusing and downright ridiculous doctrine of imamate to an ignorant layperson, and they know this, which is precisely why instead of doing the former, they resort to slandering the beloved companions of the Prophet (upon whom be peace) and fabricating stories surrounding Ali ibn Abi Talib to persuade people into thinking that the concept of a Shia1 has existed during the time of the Prophet (upon whom be peace). They bring arguments such as the Calamity of Thursday, the broken rib fabrication, fadak, Uthman’s (upon him be peace) alleged nepotism, and, most importantly: the Battle of the Camel. Although it may be unrelated to the main topic of this article, I feel it is important to highlight this fallacious tactic used by Twelver apologists. This way, you, the reader, can be better equipped to inform those who encounter such claims from a Twelver.

The First Issue: The designation “Sunni,” as historically utilized and by scholars of the East, primarily functions to differentiate the predominant group of Muslims who adhere to the general practices and traditions (Sunnah) established by the Prophet (upon whom be peace) from other sects such as the Shia and Khawarij. It does not, however, impose a strict framework of theological doctrines, especially concerning every detail of early Islamic history or the moral character of all companions of the Prophet. While conventional Sunni doctrine typically regards the companions with high esteem due to their proximity to the Prophet and their contributions to the nascent Muslim community, this does not imply that a critical assessment or skepticism about the actions of certain companions automatically disqualifies an individual from identifying as Sunni. If we regard “Sunni” simply as a semantic term used to differentiate from the Shias, this distinction does not support the Shia’s tactic.

The Second Issue: In more significant cases, such as the claim that Umar (upon him be peace) was responsible for the death of the Prophet’s daughter, Fatimah al-Zahra (upon her be peace), or other accusations that portray the companions or the wives of the Prophet (upon all of them be peace) in a negative light that makes it seem their islam is nullified, it is crucial to ensure that these claims are substantiated with reliable evidence (there is no evidence of these claims). For example, in the case of the Battle of the Camel, we see that the Twelver Shias are insistent that their viewpoint of the story is true and oftentimes asserting that the Sunni hadith corpus substaniates their claims about Aisha (upon her be peace) and Muawiyah (upon him be peace), when in reality, this is not the case at all.

See also: Clarification on the Battle of the Camel

Distorting and taking Qur’anic verses and authentic Sunni ahadith out of context, along with frequently presenting fabrications and weak Sunni narrations as ‘authentic sources,’ have often been employed as strategies within Shia polemics, and we must be careful of this. There are a plethera of material online that refutes these claims, and God willing, I plan on writing more articles systematically refuting the common arguments.

This article will be divided into 3 parts, I initially planned to structure the argument into five sections, detailing the schisms that occurred after the death of each Twelver Imam, from Muhammad al-Baqir to Ali al-Hadi. However, these schisms are often highly complex, involving differences of opinion about multiple individuals rather than solely focusing on the deceased Imam, making it challenging to present them in a straightforward manner.

Note that this article does not mention the divergence after the assassination of Ali (may God exalt his face), or the divergence after Abdullah ibn Muawiyah. The reason I do not mention these is because I wish to emphasize the latter imams in this article. For those who are interested, I have linked the book I am using as reference at the bottom of this article.

What draws our attention to this topic in question is the amount of schisms that they have amongst them. I would go as far as to say that no other religion in the world has that amount of sects.2 Unfortunately for them, this is not a trait, but rather a calamity. In particular, after the death of each imam, a new set of sects appeared, each equipped with a new methodology and a new doctrine of Imamate, and of course, claim they alone were on the correct path. It is imperative to remember that Imāmah is the building block and foundation of Shīʿism. Thus, differences of opinion regarding it cannot be tolerated, as is

tolerated in subsidiary matters.

Imam al Ashari believes that there were three primary sects, but according to his count, the total amount of sects of the Shi’a were 45. Ibn al Jawzi and Al Qurtubi were of the view that the Shi’a were 12 sects. Dā’irat al-Maʿārif, (the Arabic encyclopedia) states:

It has become apparent from the subsidiary laws of the Shīʿah that there are more sects than the seventy three famous ones. Al-Maqrīzī3 mentions that they have reached three hundred.

Dā’irat al-Maʿārif al-Islāmiyyah 14/67

As for the books on narrations, al-Kulaynī quotes a narration in al-Kāfī in which it is stated that there are thirteen sects of the Shīʿah and all of them, with the exception of one, will be in hell.4

Present day Shi’as can be catergoried into three main groups:

- Twelver Shias (The Ithnā ʿAshariyyah)

- The Ismailis (Ismāʿīliyyah)

- The Zaydi Shias (Zaydiyyah)

With that being said, let us review the history of the development of the Twelver Shi’ite sect and see if their doctrine is as clear and coherent as they make it out to be. I do not intend on analyzing each subsect in great detail, rather I present this article simply as a way to introduce the lesser known history of the shia community and the sheer number of disagreements they had.

The Schisms after the death of Muhammad al Baqir

The Mughiriyyah

When Muhammad al Baqir (upon him be peace) died, his followers became two sects. One sect believed in the imamate of Muhammad bin Abdullah bin al-Hasan who revolted against the Abbasids in Medina and was killed there.5 In fact, the proponents of this imamate believed that Muhammad bin Abdullah bin Al-Hasan was the Al-Mahdi and was not killed in reality. It was his brother, Ibrahim bin Abdullah, who told the masses to believe in the Imamate of his brother. Abu Jafar al Mansur would go on to kill him. Al-Mughira bin Saeed was one of the people who made this claim, and his followers designated him as the imam until the Mahdi arrives. This sect was called the Mughiriyyah, and Khalid bin Abdullah al Qasri, the governer of Mecca under Hisham ibn Abdulmalik, killed Mughria bin Saeed after he would go as far as to claim that he was a Prophet.

Those who believed in the Imamate of Jafar ibn Muhammad

The second sect of followers are the ones who have helped develop Twelver Shi’ism to what it is today. These were those Shias who believed that Jafar al Sadiq (upon him be peace) was next in line. The majority of those who believed in the imamate of Jafar al Sadiq remained upon this belief until he died, except a few, who abadononed him after he “hinted” the imamate of his son Isma’il bin Jafar. It is possible that the corresponding narration here is:

He said: Muḥammad bin Yaḥyā has narrated from Muḥammad bin al-Ḥusayn from Jaʿfar bin Bashīr from Fuḍayl from Ṭāhir from Abū ʿAbdillāh (a.s.). He said that Abū ʿAbdillāh (a.s.) would blame ʿAbdullāh, reprimand, and advise him, saying, “Why can’t you be like your brother? By Allah, I observe light in his face!” ʿAbdullāh said, “Isn’t my father and his father one and my mother and his mother one?” Abū ʿAbdillāh (a.s.) then said, “Ismāʿīl is from me, and you are my son.”

علي بن بابويه: محمد بن يحيى، عن محمد بن الحسين، عن جعفر بن بشير، عن فضيل، عن طاهر، عن أبي عبد الله عليه السلام، قال: كان يلوم عبد الله ويعاتبه ويعظه ويقول: ما يمنعك أن تكون مثل أخيك؟ فوالله إني لأعرف النور من وجهه! فقال عبد الله: ليس أبي أبوه واحداً؟ وأمي أمه واحدة؟ فقال أبو عبد الله عليه السلام: إن إسماعيل من نفسي وأنت ابني.

Ibn Bābawayh , al-Imāma wal-Tabṣira, p. 210.

Some claimed that Jafar al Sadiq lied to them, stating: “He lied to us, thus he is not an imam, because the Imams do not lie, nor do they say that which is not going to occur.” In particular, these people claimed that Jafar said God changed his will regarding the Imamate of Isma’il ibn Jafar.6 Sulayman ibn Jareer al Riqqi told his followers after this incident that the imams of the rafidha made up two arguments for their Shi’a to rule out any lying from their imams:

- Bada: The Imams had placed themselves in the same positions as the Prophets (upon them be peace). They told their followers that certain events would occur in the future, and if this event were to occur, then they would use this as a proof for their divinely appointed status, and if it did not, then they would say that God had changed his will.

- Taqiyyah: The same goes for Taqiyyah, which is an excuse commonly used by Twelver Shias today regarding contradictory statements that are given by the “infallible, divinely appointed Imams”. It was believed that the Imams said: “When we answered in this way we were practicing the taqiyyah. We are allowed to do this, because we know what is good for you and what protects you and us from the enemies.” How can anyone, then, catch them telling a lie, or tell their truth from their error?

Hearing this argument, some of the followers of Muhammad al Baqir moved to the camp of Sulaymān ibn Jareer and abandoned their belief in the imāmate of Jafar al Sadiq.

Jaʿfar al-Sadiq (upon him be peace) openly distanced himself from the Shia sect to such an extent that authentic narrations of his excommunication of the Shias are even recorded in their own sources.7 However, contemporary Twelver Shias attribute these actions to Taqiyyah (dissimulation, refer back to Sulayman ibn Jareer’s objection).8

The Schisms after the death of Jafar al Sadiq, Musa ibn Jafar, Ali ibn Musa, and Muhammad al Jawaad

When Jafar al Sadiq (upon him be peace) died at the age of 65, his Shi’a became six main sects:

The Nawusiyyah

Named after Ajlan bin Nawus, this sect believed that Jafar did not die and in fact will not die until he revolts and rules over the people. In other words, this sect believed that Jafar al Sadiq (upon him be peace) was the Mahdi. In particular, some quoted him saying: “If you see my head dropping from a mountain, do not believe, for I am your man.” (See also: Daftary, Farhad (2007). The Ismāʿı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 88)

The Ismailiyyah

Most of the readers are likely familiar with this denominations of Shias, the Ismailiyyahs were the ones who claimed that the man who was next in line was Jafar al Sadiq’s son Isma’il bin Jafar. Some Ismailis denied the death of Isma’il during his fathers life, saying that Jafar al Sadiq hid his son out of fear. Similarly to the Nawusiyyah, some denominations of Ismailis believed that Isma’il bin Jafar would return and would die only after he ruled the world. A significant number of people historically upheld the belief in the Imamate of Isma’il bin Jafar, and today, in 2024, approximately 12-15 million individuals continue to follow this tradition. This makes it the second-largest branch of Shi’ism, surpassed only by the Twelvers.

The Mubarakiyyah

The Ismailis gave rise to several branches, including the Mubarakiyyah, who believed that after Jafar al-Sadiq, the rightful Imam was Muhammad bin Isma’il bin Jafar. This group held that while Isma’il bin Jafar was a legitimate Imam, his imamate concluded with his death, and upon Jafar’s passing, the imamate transitioned to Isma’il’s son, Muhammad. Aside from the Sevener sect, most Ismailis today believe in the imamate of Muhammad bin Jafar. The Mubarakiyyah also argued that the Imamate after Isma’il bin Jafar could not have been Musa al Kadhim or Abdullah because the Imamate does not go among brothers after Al Hasan and Al Hussein (upon them be peace). This sect was named after the servant of Isma’il bin Jafar, al-Mubarak, who was also the chief of this sect.

The Khattabiyyah

These are the ones who revolted during the life of Jafar al Sadiq and fought against Isa ibn Musa (the nephew of as-Saffah and al-Mansur) who was the governer of Kufa at the time. This sect is named after a man by the name of Abu al Khattab who claimed prophethood. When Isa ibn Musa heard about this, he sent his forces to the mosque in Kufa when the Khattabiyyah resided. Abu al Khattab was captured and was brought to the governer of Kufa who crucified him and then burnt him. He would then send their heads to Abu Jafar al Mansur who decorated their heads at the gates of Baghdad for three days. Some of the followers of Abu al Khattab said that him and his associates were not killed, but their enemies were confused and killed others who resembled them.

I say: From my own research it seems that Abu al Khattab formed the Ismaili teaching about transferrence of spiritual authority as well as the Nusayris’ belief (whom I will get into shortly) in the manifestation of divinity in man. The tension between Abu al Khattab and al Sadiq caused Abu al Khattab’s followers to split into several smaller sects. Although Abu Muhammad al-Hasan does not mention it in his book, it is also believed that the Khatabiyyah believed that Jafar al Sadiq was God.

The Qaramita

This was another sect that emerged from the Mubarakiyyah, they were called the Qaramita, after one of their chiefs Hamdan Qarmat. This group was originally apart of the Mubarakiyyah but would go on to claim that there are only seven imams after the Prophet (upon whom be peace), ending with Isma’il ibn Jafar who is the Mahdi and a Prophet of God. Abu Muhammad al-Hasan mentions that the Qaramita also claimed that the Prophethood of Muhammad (upon whom be peace) was transferred to Ali during the event of Ghadir Khumm. (127) Abu Muhammad al Hasan also writes that the Qaramita believes that God “changed his mind” (bada) about the Imamate of Jafar and Isma’il and transfered it to Isma’il’s son Muhammad. (128) They also claimed that Isma’il ibn Jafar did not die and that he was living in the Byzantine empire. In contrast to the orthodox Islamic belief in five Cardinal Prophets (Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad, peace be upon them all), the Qarmatians recognized seven Cardinal Prophets, adding Ali and Muhammad bin Isma’il to the traditional five.

Interestingly, they based this doctrine upon the numerology of the number 7. As the heavens are seven, the levels of the earth are 7, and the man too has 7 body-parts: two hands, two legs, the dorsum, an abdoment, and a heart. The human head also has seven parts: two eyes, two ears, two nostrils, and a mouth which contains a tongue. The Qaramita believed that the “heart” of the Imams was none other than Muhammad bin Ismail. In the words of Abu Muhammad al-Hasan: “There is no doubt that those polytheists are liars, misguided, and losers.” (130)

They would also go on to claim that all things mandated by God which were emphasized by His messanger contained both esoteric and exterior meanings. All the exterior meanings of the Qu’ran and Sunnah regarding religious laws are simply analogies underscored by some esoteric meanings, which are the only ones that matter. They claim that the exterior meaning of these religious laws cause their followers torment and destruction. As I have mentioned previously of Abu al Khattab, this was also the doctrine of his followers. They allowed the killing of Muslims and claimed that they had to begin by killing those who held different doctrines about the imamate than their own doctrines. They would especially go on to persecute those who believed in the Imamate of Musa ibn Jafar and his sons after him. These Shi’as were their first priority.

The Sumaytiyyah

The fourth sect were the ones who said the next in line was Muhammad ibn Jafar, who was the son of a woman called Hamida, who was also the mother of Musa al Kadhim. It was reported by his followers that he said: He said, “I heard my father saying: ‘When you have a son, who resembles me, name him after me. For he resembles me and resembles the Messenger of Allāh, peace be upon him, and his family, and he follows his Sunnah.’” Therefore, this sect claimed the imāmate for Muhammad b. Jaʿfar and his sons after him. This sect is called the Sumayṭiyya, after one of their chiefs whose name was Yaḥyā b. Abī al-Sumayṭ.

The Fathiyyah

The fifth sect said that Jafar al Sadiq’s son Abdullah was the next imam in line. The proponents of this imamate believed this because he was Jafar al Sadiq’s oldest soon and allegedly claimed the imamate for himself. Abu Muhammad al Hasan states that those who believed in Jafar al Sadiq’s imamate also believed in the Imamate of Abdullah. (133) This sect was named after Abdullah ibn Jafar’s flat head. Although the majority of people followed Abdullah ibn Jafar’s imamate, Abdullah died without leaving an heir, and as a result, the Fathiyyah converged into acknowlegding the imamate of Musa ibn Jafar. (133) Some of the Fathiyyah began to believe in the imamate of Musa ibn Jafar during the life of Abdullah ibn Jafar, but after his death, the vast majority of the Fathiyyah began to accept Musa ibn Jafar’s imamate. This leads us to the sixth and last sect that formed after the death of Jafar al Sadiq.

Those who believed the Imamate of Musa ibn Jafar and Ali ibn Musa

Some of Jafar al Sadiq’s shias who believed in the Imamate of Musa ibn Jafar include: Hishām bin Sālim, ʿAbdullāh bin Yaʿfūr, ʿUmar bin Yazid , Muḥammad bin al-Nuʿmān Abū Jaʿfar al Ahwal (Muʾmin al-Ṭāq), ʿUbayd bin Zurārah, Jamil bin Darrāj, Ibān bin Taghlib, and Hishām bin al-Ḥakam. They firmly upheld the imamate of Musa al-Kadhim until the majority of Shi’ites gradually came to recognize his authority. This transition was notably slow, as most Shi’ites initially acknowledged Abdullah as the imam before ultimately accepting Musa’s imamate. Recall previously I mentioned a narration about Jafar al Sadiq “hinting” the imamate of Isma’il ibn Jafar:

He said: Muḥammad bin Yaḥyā has narrated from Muḥammad bin al-Ḥusayn from Jaʿfar bin Bashīr from Fuḍayl from Ṭāhir from Abū ʿAbdillāh (a.s.). He said that Abū ʿAbdillāh (a.s.) would blame ʿAbdullāh, reprimand, and advise him, saying, “Why can’t you be like your brother? By Allah, I observe light in his face!” ʿAbdullāh said, “Isn’t my father and his father one and my mother and his mother one?” Abū ʿAbdillāh (a.s.) then said, “Ismāʿīl is from me, and you are my son.”

علي بن بابويه: محمد بن يحيى، عن محمد بن الحسين، عن جعفر بن بشير، عن فضيل، عن طاهر، عن أبي عبد الله عليه السلام، قال: كان يلوم عبد الله ويعاتبه ويعظه ويقول: ما يمنعك أن تكون مثل أخيك؟ فوالله إني لأعرف النور من وجهه! فقال عبد الله: ليس أبي أبوه واحداً؟ وأمي أمه واحدة؟ فقال أبو عبد الله عليه السلام: إن إسماعيل من نفسي وأنت ابني.

Ibn Bābawayh , al-Imāma wal-Tabṣira, p. 210.

Interestingly, if we go to Al-Kholyani’s Al Kafi, we see this same narration, but we notice in particular the omission of a certain name:

Al-Kulaynī said: Muḥammad bin Yaḥyā has narrated from Muḥammad bin al-Ḥusayn from Jaʿfar bin Bashīr from Fuḍayl from Ṭāhir from Abū ʿAbdillāh (a.s.). He said that Abū ʿAbdillāh (a.s.) would blame ʿAbdullāh, reprimand, and advise him, saying, “Why can’t you be like your brother? By Allah, I observe light in his face.” ʿAbdullāh said, “Why? Isn’t my father and his father one? Isn’t my mother and his mother one?” Abū ʿAbdillāh (a.s.) then said, “He is from me, and you are my son.”

قال الكليني: محمد بن يحيى، عن محمد بن الحسين، عن جعفر بن بشير، عن فضيل، عن طاهر، عن أبي عبد الله عليه السلام، قال: كان أبو عبد الله عليه السلام يلوم عبد الله ويعظه، ويقول: ما معك أن تكون مثل أخيك، فوالله إني لأعرف النور في وجهه؟ فقال عبد الله: أليس أبي وأبوه واحداً، وأمي وأمه واحدة؟ فقال له أبو عبد الله عليه السلام: إنه من نفسي وأنت ابني.

Al-Kulaynī’s al-Kāfī, 2/69

Foul play is clearly evident in this case. It cannot simply be attributed to an oversight by the narrator, particularly Muhammad ibn Yahya, in omitting the most significant part of the narration. It is also plausible that this distortion was deliberately introduced by Al-Kulaynī to fabricate additional “evidence” in support of Musa’s imamate. We leave the analysis of this discrepency up to the reader.

Some Shias believed that Abdullah was still a legitimate imam regardless of the fact that he left no heir, but these people would also go on to accept the imamate of Musa ibn Jafar as well. Among these are ʿAbdullāh bin Bukayr bin Aʿyan, ʿAmmār bin Mūsā Al-Sābāṭī, and few others, who followed them. (135) Nonetheless, the Shia communities had doubts around his (Musa’s) Imamate when he was imprisoned a second time and died in captivity. Five sects emerged after his death.

The Qatiyya

One sect believed that Musa ibn jafar was fed poisonous grapes and died in captivity. They said that the imam after Musa ibn Jafar was Ali al Ridha. This sect was called the Qatiyyah because they affirmed the death of Musa ibn Jafar and that Ali ibn Musa was next in line. This sect would go on to form the Twelver Shia sect.

Another sect believed that Musa ibn Jafar did not die in captivity, but rather he will only die once he rules the world from east to west. That is, this sect believed that Musa ibn Jafar was the Mahdi. In fact, to be more specific, this sect believed that Musa ibn Jafar escaped and went into hiding, the ones who imprisoned him simply claimed that he died to avoid confusion. Others said that he died but would return from death. Some claimed that he did in fact return from death already and that he is hiding in an unrevealed location, giving orders to his close followers (sound familiar?). Others said that he died but is the Mahdi and will return from death at a determined time to fill the world with justice.

The Waqifa

Some claimed that Musa ibn Jafar was not killed and rather was lifted up by God into his domain (similar to what Christians believe about Jesus) all of the people who held this belief were called the Waqifa, which means “The Halting Sect”. This is because they stopped at Musa ibn Jafar as the final imam and they did not follow an imam after him. Those who claimed that Musa ibn Jafar was not killed in captivity would indeed reject the imamate of Ali al Ridha and all of his descendents, and would argue that they were deputies of Musa ibn Jafar rather than imams. Another sect claimed uncertainty regarding whether Musa ibn Ja’far was dead or alive, citing numerous stories portraying him as the Mahdi. These individuals continued to follow the imamate of Musa ibn Ja’far until confirmation of his death was provided. They even went so far as to assert that Ali al-Ridha had appointed himself. (139)

The Bishriyyah

This sect was named after the followers of Muhammad ibn Bashir, who lived during the time of Imam Musa ibn Jafar and his son Imam al Ridha according to Rijal al Kashshi pp. 477-4839, both of them cursed him and wished him the absolute worst type of death. This group said Musa ibn Jafar did not die or enter any jail, and that he was alive and that he was al-Mahdi, and that before going into hiding, he appointed Muhammad ibn Bashir as his heir and taught him everything that his followers would need. Before ibn Bashir died, he designated his own son as the imam. This line of imams claimed that Ali ibn Musa and the rest of his descendants were not legitimately born and accused them of blasphemy for claiming imamate. It is also important to note that this sect permitted incest and homosexuality, as well as believing in the doctrine of metempsychosis, saying that all the imams are actually one person.

Al-Nawbakhti writes that the followers of Imam al Ridha were divided after his death and became several sects (142). This is not far-fetched, Irreconcilable disagreement occurred between the Shīʿah concerning the Imāmah of Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī (al Jawad) as he had not yet reached maturity when his father died. The reoccuring pattern of disagreement continues as some groups argued that only a mature Imam is permissible.

The Mu’allifa

This sect acknowledged the Imamate of Al-Ridha, but after his death, they returned to the belief that the Imamate terminated with Musa ibn Jafar.

The Muhadditha

This sect entered among those who acknowledged the imamate of Musa ibn Jafar and Ali ibn Musa, as Al-Nawbakhti puts it: “for the sake of worldly goods.” (143) This is likely due to the fact that Al-Mamun designated Ali ibn Musa has his heir.

One of the progeny of Al-Hussein claimed Imāmah during Al Jawad’s lifetime, a man by the name Muḥammad ibn al-Qāsim ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿUmar ibn ʿAlī Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib. Al-Tabari, Ibn al Athir, and others mention this.10

The Nusayris

The reason for the immense number of divergences of sects during this time is, as mentioned previously, the age of the Imams when their predecessor died. If God were to mandate the obedience of non-adults, it would be possible that He burdens non adults with religious duties. So it was a very popular belief among the Shiites that a non adult would not be able to comprehend the intricacies of jurisprudence and the divine law, in addition to all the prophetic teachings of the Prophet (upon whom be peace) as well. A group of the Shi’ites who believed in the Imamate of Ali ibn Muhammad (Ali al-Hadi) deviated during his life by claiming prophethood for a name named Muhammad ibn Nusayr al Numayri. Al Kashshi reports that he claimed prophethood for himself. (Rijal al Kashshi, pp. 520-521)

The Al-Nusayriyya sect was named after him, as of 2024, there are approximately four million members of this group in the world. Ibn Nusayr believed in metempsychosis and made claims about Ali al Hadi’s divinity. It is also reported that he permitted homosexuality among men according to Al-Nawbakhti. One of the supporters of ibn Nusayr was a man named Muhammad ibn Musa ibn al-Hasan ibn al-Furat, when he fell ill, he told those who asked him about his heir that he designated Ahmed. However, it was unclear which Ahmed he was referring to, his followers diverged into three sects, Al-Nawbakhti refers to all three as “the Numayriyyah” which likely still refers to Nusayris. Al-Shahrastānī speaks of the Nuṣayriyyah is his al-Milal. He describes their creed, asserting that they believe:

The Schisms after the death of Ali al Hadi

When Ali ibn Muhammad ibn Ali ibn Musa al-Ridha died, one sect of his followers believed in the imamate of his son Muhammad ibn Ali who died during his fathers life, they claimed he did not die, citing that his father designated him for the imamate after him, and that the imam is not allowed to lie. They claimed he is al-Mahdi which is a similar claim to that of the followers of Ismail ibn Jafar.

Those who believed in the Imamate of Hasan al Askari

The rest of the followers believed in the imamate of Hasan al-Askari, however, a small circle followed his brother Jafar ibn Ali. Al Nawbakthi writes that Hasan al-Askari’s imamate lasted 5 years and 8 months, he died without leaving an apparent son. This lead to one of the worst divergences of sects in the development of Shia doctrine, which I will dedicate a completely different article to.

Conclusion

The development of the doctrine of the Twelve Imams was far from straightforward. While Twelver Shi’ites assert that the concept of the imamate is clear and well-defined, historical evidence suggests otherwise. Early Shi’ite communities were deeply divided, with little consensus on key beliefs. Many of them held views that coincide significantly from those of modern Twelver Shi’ites, such as the idea that certain Imams did not die but instead went into hiding. These similarities are evident in the modern doctrine of the hidden Twelfth Imam. The doctrine appears to have been constructed by incorporating specific beliefs from various divisions, such as the concepts of bada and taqiyyah. These ideas initially emerged during the schisms following the death of Muhammad al-Baqir. Notably, Ja’far al-Sadiq himself was unapologetically against the Shi’ite factions. With that being said, it is very important to learn about these divisions in the early shia community. These historical disputes reveal that the doctrine of the imamate was neither clear nor firmly established. This lack of clarity poses a significant challenge for Twelver Shi’ites, as the doctrine of the imamate forms the very foundation that their religion stands on

Below is a PDF of Al-Nawbakhti’s Kitab Firaq al-Shi’a. I omitted a lot of material from the book and I would highly recommend all to read it in its entirity. The list of sects that he mentions in this book is, unsurprisingly, not exhaustive. (See also: Wikipedia: List of Extinct Shia Sects)

- When I mention “Shia” here, I am not referring to the Shia’t Ali, those who stood by Ali ibn Abi Talib during the first conflict in the Muslim world. Instead, I am using the term “Shia” in its modern-day context. ↩︎

- The difference of opinions among Sunnis which lead to the 4 schools of jurisprudence are not sects. ↩︎

- Al-Khuṭaṭ 2/351 ↩︎

- Uṣūl al-Kāfī 4/344. Al-Majlisī, classified this narration to be Ḥasan (reliable). Mir’āt al-ʿUqūl 4/344 ↩︎

- https://en.wikishia.net/view/Muhammad_b._Abd_Allah_b._al-Hasan ↩︎

- Note that we Muslims do not believe such nonsense about Jafar al Sadiq or any of the Shi’ite claims about the righteous Ahlul-Bayt. ↩︎

- Ikhtiyar Ma’rifat al-Rijal also known as Rijal al-Kashshi, p. 427 ↩︎

- Sharh Usul al-Kafi by Muhammad Salih al-Mazandarani, vol. 5, pg. 323 ↩︎

- This is the citation in Al-Nawbakhti’s book. ↩︎

- Maqātil al-Ṭālibiyyīn, pg. 577 ↩︎