As I have mentioned previously, it is important we understand why we accept certain hadith and why we reject others. If we did not have a criteria to understand what narrations are authentic and what narrations are not, we would likely be taking our religion from liars. The science of rijal is a branch of hadith sciences that discusses the qualities of the hadith transmitters, especially their reliability in hadith transmission, and the related criteria and rules. The science of rijal in Sunni literature is airtight, and account for numerous circumstances to ensure that we, as muslims, only take hadith that can truly be attributed to the Prophet (upon whom be peace), his companions, and his family. I have mentioned in a previous article several circumstances that Sunni rijalists take into account to determine the authenticity of a narration that Shi’ite rijalists do not entertain. I will mention them again:

- Sunnis have authored books that revolve around good narrators that have become weak with age. Shias, on the other hand, have never done such a thing because they didn’t entertain such a possibility.

- Sunnis have authored books on chain disconnections. They would list out names of narrators and give evidences that these narrators didn’t meet their teachers. Shias, on the other hand, never entertained the possibility that a student probably never met his teacher.

- Sunnis have authored books on tadlees. This revolves around students that have met their teachers, however didn’t narrate a specific hadith from them. Shias, on the other hand, never entertained the possibility that a student may have not heard one of the narrations of his teacher.

- Sunnis have a significant upper hand when it comes to the documentation of dates. Because of this, scholars like Al-Tusi had to rely on work by Sunni scholars when stating the year in which a Shia narrator died.

See: Shia Claims about Sahih al Bukhari and Sahih al Muslim

Again, this list is not exhaustive, but I believe it gets my point across. This article, however, is not focused on these points but rather on two specific pieces of Shi’ite literature: Rijal al-Tusi, and Rijal-al-Najashi.

Al-Tusi (d. 460 AH) and Al-Najashi (d. 450 AH) are the two main Shi’ite authorities on Rijal. However, both of these men did not witness or encounter most of the transmitters they endorsed/condemned. The gap between them and the transmitters they often mentioned was often more than two centuries long.

The grand Ayatollah Al-Khoei thus wrote that al-Tusi and al-Najashi did not issue their verdicts based off their own judgement, rather, al-Khoei believed that they simply transmitted the endorsements/condemnations from earlier sources that actually witnessed these transmitters. However, this appeal results in a number of new errors, the most important one is that neither of these men listed these hypothetical sources that relayed to them these verdicts on the reliability of transmitters. It is clear that al-Khoie’s position was merely conjecture. Any logical historian is thus incapable of verifying the authenticity of these claims and verdicts.

As a result of this, Shi’ite scholar of hadith, Asif Mohseni, presents this dilemma in his book:

The problem is that their endorsements and condemnations of a transmitter, along with anything else they mention about the transmitters, come with a gap in time. However, they do not list the transmitters between them [till that period] for us to analyze whether they were reliable, weak or unknown transmitters. Accepting such time-lapsed approvals of transmitters is unjustified unless we are to give them the benefit of the doubt and assume that they only transmitted from reliable transmitters without listing them. In that case, how can we accept their statements? Why don’t we ask about whom they transmitted [these endorsements] from? If anyone were to find me a solution to this dilemma, I would offer him a sum of money and I would be very thankful, for this dilemma makes ilmur-Rijaal an unreliable discipline from a logical and religious standpoint.

Asif Mohsini’s Buhuth fi ‘Ilm Al-Rijal. p. 58

Mohsini clearly states that this dilemma is fundamentally undermining he core of Shi’ite Ilm Al-Rijaal. It is something so important that Mohsini even offered money to the one who could come to a conclusion about this dilemma. If there is no evidence proving that Al-Tusi and Al-Najashi relied on authentic chains tracing back to transmitters from the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th centuries when forming their verdicts, then their opinions on transmitters from these periods are objectively unreliable because it would seem that these rijalists are acting upon conjecture or simply making their verdicts up. It then follows that the entire process of authentication in Twelver hadith sources is potentially jeopardized as a result of this dilemma.

This dilemma ultimately manifests in the endorcement of forgers and weak narrators (i.e. blatant liars). Given the flawed approach to ‘Ilm Al-Rijal adopted by the Shia, it is unsurprising that Shi’ite biographical sources have ended up endorsing a range of forgers, liars, and weak transmitters. For one, consider the following example of Asram b. Hawshab. Ibn Hajar, Abu Hatem Al-Razi, Al-Nasa’i, Al-Bukhari, Al-Muslim, Al-Jawzajani, and Ibn Hibban were all in agreement that Asram b. Hawshab was weak in hadith. Some called him a liar, some called him a fabricator.1 Al-Jawzajani stated that he met Asram b. Hawshab and transcribed hadiths from him, yet he concluded that he was weak. However, Al-Najashi, who came two centuries later, never met him, however, randomly declared him to be reliable.2 We have mentioned previously that Sunni sources predate Shi’ite sources, and all the critics of Asram b. Hawshab predate Al-Najashi. It is important to note that Asram b. Hawshab was not regarded as a Rafidhi (Twelver Shi’ite) by those who criticized him, he transmits a report demonstrating the virtues of Abu Bakr, ‘Umar and ‘Ali3, yet he was still declared to be a forger by Sunni scholarship, hence, there was no sectarian bias in play for those who criticized him.

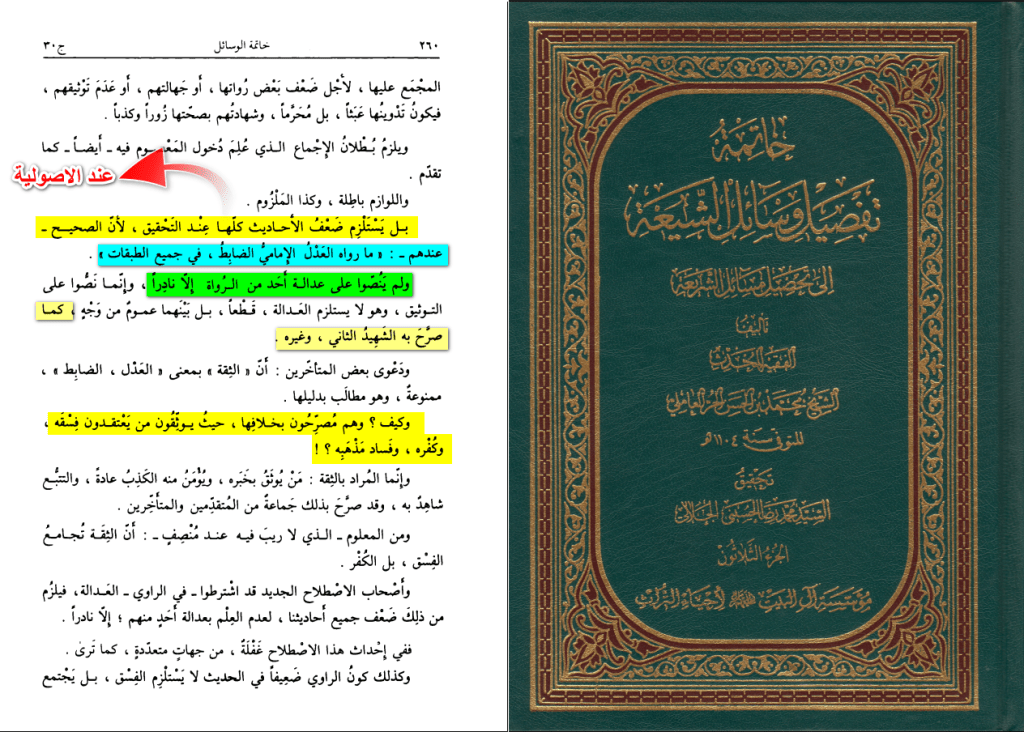

These arguments are relevant to virtually every case where Shi’ite authorities have endorsed transmitters who were criticized and condemned by Sunni hadith critics. This phenomenon underscores the arbitrary nature of authentication in Shi’ite sources and the problematic conclusions that arise from this methodology. This is why a number of Akhbari Shi’ite believe that if the science of rijal were applied to the Shiite narrations, all of them would fall:

And as I have mentioned previously, Ibn Sirin once said:

“Indeed, this knowledge is religion, so be careful from whom you take your religion.”

wonderful

LikeLiked by 1 person